Click in the button to see annotations by other readers and to add your own.

Click in the button to see annotations by other readers and to add your own.

Politics and social media

Daniel Gayo-Avello

Get it on PDF format

Foreword

Every one is son of his time; so philosophy also is its time apprehended in thoughts.

It is just as foolish to fancy that any philosophy can transcend its present world,

as that an individual could leap out of his time or jump over Rhodes.

G.W.F. Hegel (translated by S.W. Dyde)

What has been will be again,

what has been done will be done again;

there is nothing new under the sun.

Prologue

At first sight, politics and social media could appear to be a rather concrete and well-delimited topic. However, that’s only true if you are reading these words not long after their publication—let’s say in 5 to 8 years. If that’s the case, it is not unlikely that you have heard of Twitter or Facebook, and you may even had got an account (a ‘profile’, in the parlance of the age), while Google+, MySpace, Orkut and Second Life are probably long forgotten services. At the same time, blogs, wikis and email are probably still alive and kicking, no matter the fate that Blogger, Wordpress, Wikipedia and Gmail may have faced. You probably remember president Obama and you may have heard of his historical campaign of 2008, but you may have no clue about what Big Bird, horses, bayonets and binders full of women have to do with the US Presidential Elections of 2012. It is also not unlikely that ‘social media’ as a buzzword had faded into oblivion, and a different one had been coined to describe something ‘entirely new’ that is, below the surface, ‘more of the same’.

Does this mean that this book has a ‘shelf life’? Should you discharge it after, say, 2025? I hope not. And I hope that, not because of my ‘precognoscency’, but because of my aim to broaden that ‘social media and politics’ topic by looking both backwards and sideways. Looking backwards, because I’ll revisit the many different ways in which people have been interacting, engaging in politics, and organizing themselves long before so-called ‘social media’ and ‘Web 2.0’. And looking sideways, because there are much more in politics than just electoral campaigns and voting.

Thus, if you are using any form of Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) to learn of other people’s ideas on governance, express yours, and maybe influence others to organize actions in order to move forward your point of view, then this book can be of your interest. You will find than your elders were not that different from you, and that except for computers (and maybe smart watches, or in your case ‘carbon sockets’ behind your ears—Gibson, 1984) you (and we before you) have been facing many of the problems that Solon and Pericles tackled with more than 2,500 years ago.

That said, this book is a product of its time and, therefore, you won’t find references beyond 2015; moreover, you will read plenty about cyberspace, forums, Usenet, email, blogs, Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, or YouTube.

What do I talk about when I talk about politics?

Although it can be implied from its contents I think it is much better to explicitly state it: this book is focused in political uses of social media, not in politics affecting social media, or politics within social media (cf. Margolis and Resnick, 2000: pp. 8-21).

More concretely, this book deals with politics as commonly understood in liberal democracies. Because of that, attention is paid to individual political participation; the way in which different political actors such as parties, elected officials, legislatures or nonprofit organizations use social media; the way in which social media can be used to ascertain different kinds of public opinion; or the role that social media plays during elections.

There are two main reasons to focus on liberal democracy: First, virtually all of the technologies under the umbrella term ‘social media’ have been devised in democratic countries and, indeed, it has been argued that such tools can act as democratic catalyzers in authoritarian regimes. Second, as Churchill said, “democracy is the worst form of Government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time” or, as it has been rather convincingly argued, liberal democracy is the most satisfying governance system and, quite likely, the definite one (Fukuyama, 1992).

This by no means implies that liberal democracies are flawless: virtually all of them suffer serious problems and people worldwide have been asking for changes to improve the current state of their respective democracies. Inevitably, social media has also played a role in such struggles and some voices claim that such media can help to revitalize democratic culture in the future, or even change it entirely.

On another hand, the point of view of Fukuyama on liberal democracy is not free of criticism, particularly by assuming that liberal democracies are inextricably linked to economic liberalism (Derrida, 1994: p. 72). Indeed, a fair amount of discussion has been devoted to the question of whether privately-owned social media can help democracy or if they, conversely, may be harmful.

There are still additional caveats to Fukuyama’s thesis that liberal democracy will eventually flourish worldwide, and some of them are provided, rather surprisingly, by Fukuyama himself (2014), albeit an older and maybe wiser one. He identifies two worrisome issues: To start with, some authoritarian regimes did not simply disappear during the 1990s but, instead, they somehow transmuted by incorporating liberal economic elements without changing the political sustrate. Then, some democratic countries have been increasingly incorporating authoritarian elements. Needless to say, social media are being used—albeit with more or less difficulties—in such countries and, thus, a review of their political implications under authoritarian regimes is de rigueur.

Finally, there are two threats to democracy that lie in opposite ends of the political spectrum.

At one end we have terrorism which, at the moment of this writing, has got as its most worrisome example jihadism. However, the truth is that the purported goals or credo of terrorist groups are of little interest because all of them share a great deal of common features, including their employment of social media. Besides, it does not matter how dreadful terror acts may seem, they are “a form of of political communication, intended to send a message to a particular constituency” (McNair, 2011); hence, this book would be incomplete if it did not include terrorism when discussing contentious politics and social media.

The other threat to democracy is pseudo-activity which Žižek (2008: p. 183) describes as:

“The urge to ‘be active’, to ‘participate’, to mask the nothingness of what goes on. [...] Those in power often prefer even a ‘critical’ participation, a dialogue, to silence - just to engage us in ‘dialogue’, to make sure our ominous passivity is broken.”

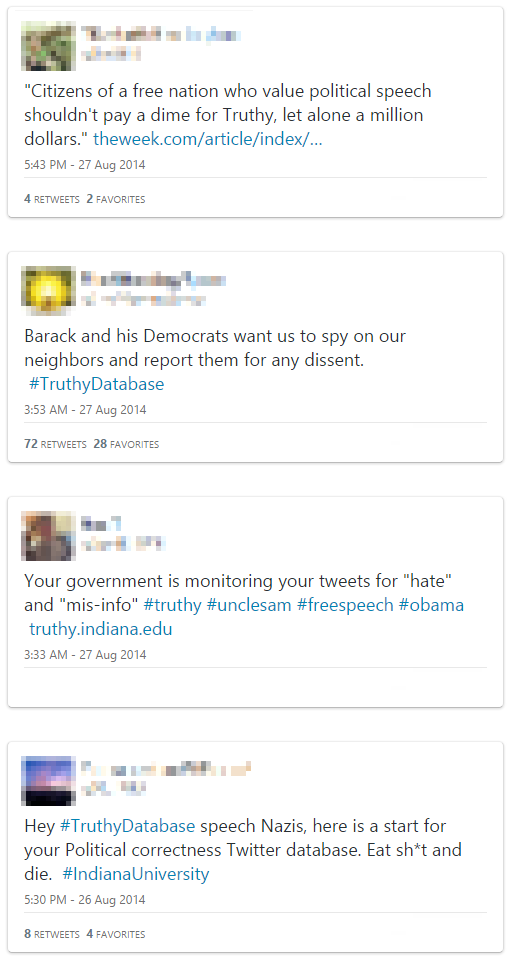

The problem of pseudo-activity regarding politics in social media is covered in this piece from a number of perspectives: under its most conventional form of ‘slacktivism’ or ‘clicktivism’, but also when describing the nature of communicative capitalism and its impact when interpreting social media as a potential deliberative realm, or when reviewing the subtleties of censorship under networked authoritarianism.

So, in short, my coverage of politics encompasses the different aspects of democratic life; the behavior of the different actors operating under, for, and against democracy—including slacktivists, contenders, and terrorists; and the way in which democracy can eventually succeed over authoritarianism.

What do I talk about when I talk about social media?

It is probably no exaggeration to say that there are as many definitions of ‘social media’ as researchers and practitioners working in the field. However, as I have done with ‘politics’ I want to devote some time to explicitly state which kind of ‘social media’ I am discussing in this book. Hence, I will start with two definitions which are almost ten years apart: the first one is the first entry about ‘social media’ in Wikipedia—a social media itself:

“Social Media is the term used to describe media which are formed mainly by the public as a group, in a social way, rather than media produced by journalists, editors and media conglomerates.” (Benvie, 2006)

The second one is the definition provided by Hogan and Melville (2015):

“Social media represent a set of communication practices that can typically be described as ‘many-to-many.’ In contrast to broadcast media, consumers are typically also producers. In contrast to in-person communication, audiences are often ambiguous or underspecified.”

Both definitions share the concept of ‘user generated content’ but, apart from that, they are quite different and, in all probability, you are already making some addenda to both. Indeed, it seems that every definition of social media is somewhat incomplete without being accompanied by ostensive definitions.

For instance, the second version of Wikipedia’s definition for social media (also by Benvie) included as examples: “blogs, Podcasts, Vlogs, Wikis, MySpace, YouTube, Second Life, Digg, Memeorandum, del.icio.us, Reddit, Flickr, Tailrank and Newsvine”.

The more recent piece by Hogan and Melville mentions “collaborative encyclopedias such as Wikipedia, social network sites (SNSs) Facebook and Twitter, photo-sharing sites Instagram, and social news site Reddit.” They also point out that “technologies such as instant messengers, and to some even e-mail are considered social media.”

Thanks to those lists of examples a second feature of social media, one that is usually implicitly assumed, is made much more notorious: social media requires a communication network. In fact, without such a network (internet at the moment of this writing and phone lines before) we cannot properly talk about social media.

Still, there is a crucial point that has been barely hinted: the social part of social media. Going on with prior definitions it is not until the fifth revision of Wikipedia’s entry that some clues on the meaning of ‘social’ are provided:

“people create and share with each other [opinions, insights, experiences and perspectives]”

On the other hand, Hogan and Melville argue that social media are characterized by ‘many-to-many’ communication (in contrast with one-to-many, i.e. broadcasting, or many-to-one, i.e. voting or petitions), and ‘non addressed’ or underspecified audiences (e.g. “all Facebook friends, Twitter followers, readers of a bulletin board, and so forth”).

So, in short, the social part of social media is determined by the particular relations that are established between its users when creating and consuming contents. Everyone can be a creator with their own audience and, at the same time, being part of the audiences of a variety of other users.

Clearly, many of the tools developed in the early XXI century during and after the so-called ‘Web 2.0 revolution’ fit such definitions of social media. Some of them, particularly ‘social networking sites’, are at the moment of this writing considered as the most prominent example of social media and, in some cursory reviews, the only one.

Nevertheless, different services that were available long before ‘social media’ also fit prior definitions. I am not talking about precursors or prior art, I am talking about systems and tools that were (and some of them still are) social media but were known by different names and, somehow, have been eclipsed by the fanciness of ‘social media’ as a buzzword.

For instance, Dahlberg (2015) suggests 1995 as the moment when Web-based digital media that were social media in all except for the name reached a peak, but he also mentions a number of applications predating the Web that deserve the consideration of social media: “bulletin board systems (e.g., Usenet and FidoNet), synchronous online chat (e.g., Internet Relay Chat), multi-user real-time virtual worlds, and, [...] [the] e-mail list”.

Indeed, he is not alone in the vindication of social media before ‘Social Media’; in this regard, the words by Nancy Baym (2015) are not only doing that, but providing a rationale for the coinage of a new term to describe as anew something that was already available:

“Any medium that allows people to make meaning together is social. There is nothing more ‘social’ about ‘social media’ than there is about postcards, landline telephones, television shows, newspapers, books, or cuneiform. There are distinctive qualities to what we call ‘social media’, but being social is not among them. Long before ‘social media,’ the Internet was used to do what Facebook’s mission statement promises. If the words ‘social’ and ‘media’ don’t describe anything distinctive, what cultural work does the term ‘social media’ do?

It obscures the unpleasant truth that ‘social media’ is the takeover of the social by the corporate. ‘Social media’ happened when companies figured out how to harness what people were already doing, make (some of) it a bit easier, call it ‘content,’ and funnel our practices into their revenue streams. The term ‘social media’ puts the focus on what people do through platforms rather than critical issues of ownership, rights, and power.”

It must be noted that this perspective is not particular of Baym but it is not commonplace. However, I think that the fact that a fair amount of political actions are being conducted within privately-owned spaces should be a matter of concern for anyone with a real interest in politics. Actually, the fact that social media is a set of different ‘walled wardens’ can be the most definitory issue of the platforms used during the early XXI century.

But let’s go back to social media before ‘Social media’, which were those services? The truth is that the ecosystem was pretty varied: before the advent of the Web bulletin board systems (BBS), Usenet, Internet Relay Chat, and listservs were very popular (mainly during the late 1970s and 1980s). With the expansion of the Web (early 1990s) services mirroring most of the features of pre-Web platforms appeared, in addition to new tools such as wikis, blogs, or social bookmarking and tagging tools (mid-late 1990s). Eventually, social networking sites appeared (late 1990s and early 2000s) and ‘social media’ was coined.

It must be noted, however, that although older services have lost popularity they have not disappeared and, at the moment of this writing, most of them are available. Indeed, the current social media ecosystem can be seen as a number of layers accumulated along the last decades, each of them with its own age of glory and its idiosyncratic buzzword.

Some of such buzzwords are mostly interchangeable with ‘social media’ while others exhibit certain amount of overlap, or refer to some feature or subset of current social media. The most popular, in approximate chronological order, have been: Computer Conferencing, Computer-Mediated Communication, cyberspace, the Net, the Web, and Web 2.0.

So, in short, I use ‘social media’ to describe any communication tool that allows users to consume, share and create multimedia contents which are addressed to unspecified audiences, in a potentially many-to-many fashion. Although not a prerequisite, the most popular social media platforms during the early XXI are privately-owned, and virtually all of them incorporate to some extent social-networking features (such as user profiles and lists of ‘friends’).

Such a broad interpretation clearly covers social-networking sites (SNS) such as Facebook or Twitter, but also the blogosphere, listservs, chatrooms, IRC, or Usenet to name just a few. Hence, although I will mainly cover recent research performed on SNS I will also rely on literature dealing with the intersection of politics and this much broader interpretation of social media.

Why the intersection of politics and social media is crucial?

The whole point of this book is that interaction between social media and politics is not simply important, but crucial. However, to support such a strong claim I need to digress a little.

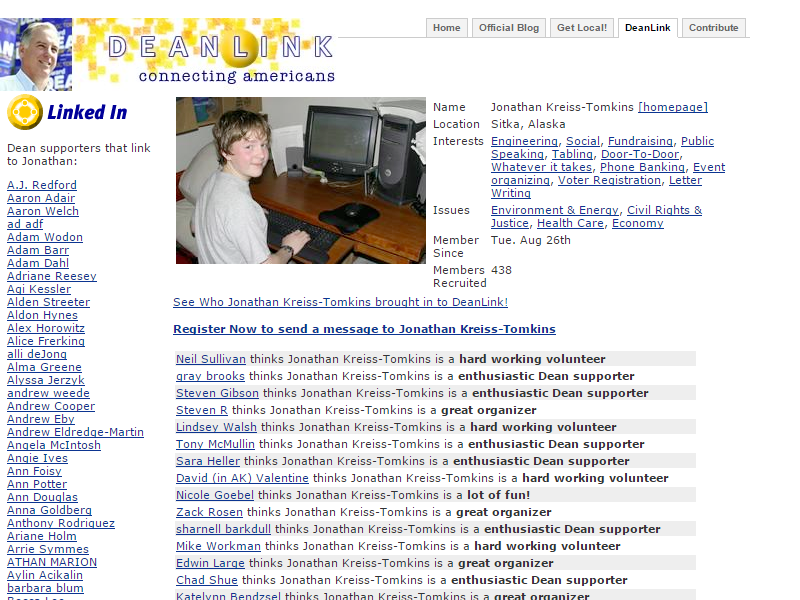

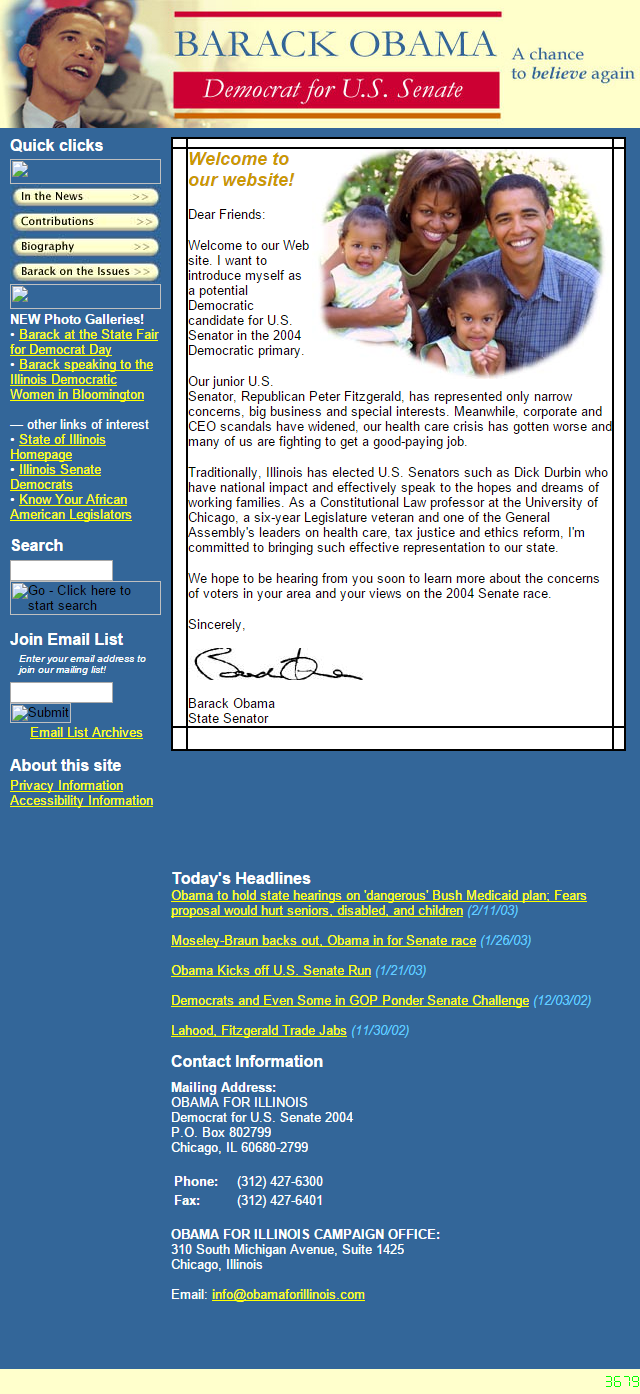

As I have suggested in the prologue, a cursory approach to the topic could imply a mere interest in social networking sites and elections. If that was the case, a literature review could trace maybe a decade worth of material that would be mainly focused in the United States, and would probably have a heavy emphasis in president Obama’s campaigns. As such, it could be considered interesting, even fashionable, but not universally appealing or generalizable beyond the realms of Facebook or Twitter, or the idiosyncrasies of the USA.

However, such an approach would have been shortsighted, and by focusing in case studies we would risk missing the big picture. A broader interpretation of both politics and social media allows us to go beyond single case studies to, firstly, find deeper long-term implications of the use of computer-mediated communications for political action, and, secondly, avoid repeating prior mistakes (and ubris).

At the moment of this writing, it seems that some social media researchers and practitioners are somewhat intoxicated by what I call ‘social media exceptionalism’. That is, social media—normally reduced to SNS—is considered something entirely new which is to revolutionize every aspect of our lives, including of course politics.

Such exceptionalism is normally received with skepticism and, hence, a dialectical fight eventually arise. A broader interpretation of social media helps to better contextualize this kind of claims and debates, and tone down the social media exceptionalism discourse. Actually, the debate about the purportedly beneficial impact of computer-mediated communications (i.e. social media) in politics, and its corresponding replica can be traced back at least to the mid-1980s.

For instance, Winner (1986: pp. 98-99, 105) said about cyber-optimists:

“In countless books, magazine articles, and media specials some intrepid soul steps forth to proclaim ‘the revolution.’ Often it is called simply ‘the computer revolution’ [...] Other popular variants include the ‘information revolution,’ ‘microelectronics revolution,’ and ‘network revolution.’

…

Computer scientist J. C. R. Licklider of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is one advocate especially hopeful about a revitalization of the democratic process. [...] ‘The information revolution,’ he exclaims, ‘is bringing with it a key that may open the door to a new era of involvement and participation. The key is the self-motivating exhilaration that accompanies truly effective interaction with information through a good console through a good network to a good computer.’ It is, in short, a democracy of machines.

...

Taken as a whole, beliefs of this kind constitute what I would call mythinformation: the almost religious conviction that a widespread adoption of computers and communications systems along with easy access to electronic information will automatically produce a better world for human living.”

Other scholars made similar criticism while focusing in particular instances of social media. For instance, while discussing Usenet newsgroups and email listservs, Streck (1998) said that as any other human product they are subject to human limitations and, hence, in spite of the promises of cyber-optimists, cyberspace would not produce equality or diversity but “a world much like our present one: a heterogeneous place of community, isolation, prejudice, love, hate, intelligence, stupidity, culture, commerce, respect, disregard and just about everything else that makes life at once worth living and almost more than we can stand.”

I guess that this sort of criticism sounds familiar to you but applied to social networking sites; hence, you will neither find novelty in the arguments supporting their purported democratizing power. For instance, Rheingold (1993: p. 133) said about bulletin board systems:

“If a BBS (computer Bulletin Board System) isn’t a democratizing technology, there is no such thing. For less than the cost of a shotgun, a BBS turns an ordinary person anywhere in the world into a publisher, an eyewitness reporter, an advocate, an organizer, a student or teacher, and potential participant in a worldwide citizen-to-citizen conversation.”

And he said the following about being informed in real time about ongoing events (Rheingold 1993: p. 283):

“Information and disinformation about breaking events are pretty raw on the Net. That’s the point. [...] With the Net, during times of crisis, you can get more information, of extremely varying quality, than you can get from conventional media. [...] None of the evidence for political uses of the Net thus far presented is earthshaking in terms of how much power it has now to influence events. But the somewhat different roles of the Net in Tiananmen Square, the Soviet coup, and the Gulf War, represent harbingers of political upheavals to come.”

You could simply replace ‘BBS’ or ‘the Net’ by ‘Twitter’, ‘Facebook’, ‘YouTube’ or virtually any other social media service and you would not notice that the argument is not contemporary but more than 20 years old. Replace ‘Tiananmen Square’, ‘Soviet coup’, ‘Gulf War’ with ‘Arab Spring’, ‘Euromaidan’, and ‘War on Terror’, respectively, and you are not reading about old-fashioned cyberspace but about the huge potential of Twitter as a news source.

Even the threats to the presumed power of social media have been warned a number of times. For instance, Strangelove (1994) said about email, censorship and control:

“E-mail, as a metaphor for networked, global, uncensored communication, is already under attack by the state (through the Clipper chip legislation--an attempt to provide wiretap capability for all electronic communication). E-mail, Internet-based communication, is clearly potentially subversive as it allows bi-directional, unfiltered, uncensored mass communication.”

Rheingold (1993: pp. 298-299) also mentions the chances of exploiting computer-mediated communication “as means of surveillance, control, and disinformation” and provides an additional sort of criticism that perfectly applies to contemporary social media: its commoditization. Indeed he made some poignant but accurate predictions about our contemporary ‘free-model’ in social media (Rheingold, 1993: pp. 312-313):

“You won’t need a dictatorship from above to spy on your neighbors and have them spy on you. Instead, you’ll sell pieces of each other’s individuality to one another. [...] The most insidious attack on our rights to a reasonable degree of privacy might come not from a political dictatorship but from the marketplace. [...] These professional privacy brokers have begun to realize that a significant portion of the population would freely allow someone else to collect and use and even sell personal information, in return for payment or subsidies.”

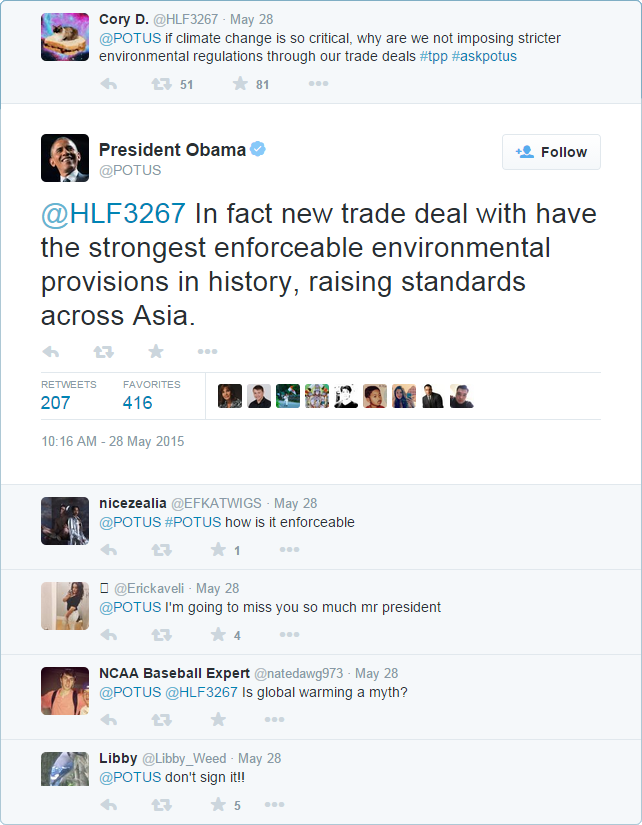

You may be wondering what is the point of this detour to the late XX century. Simple: I want to stress that contemporary social media and politics is no more about Twitter and the @POTUS account than 1990s’ cyberspace and politics was about president Clinton and vice president Gore announcing they would be reading email. If we keep looking at the proverbial finger (i.e. the fashionable case studies about Twitter, Facebook, and so on) we will miss the Moon: the ongoing work that has been conducted during the last three decades to understand how to exploit a powerful set of tools to involve citizens worldwide in actual democratic political action, and to avoid the two dire threats menacing such high hopes: authoritarian control and market commoditization. Those two simple ideas are the justification for this book.

Which is my position and which are my goals with this book?

Along this piece I will provide (at least that is my aim) a balanced review of the literature, but that does not imply that I will act as a dispassionate observer. I have a strong point of view regarding the interaction of social media (whatever its name) and politics, and my position cannot be detached from my analysis of what has been done in the field and what will be likely done in the future. I think that my position will be pretty obvious while reading the book but, as I have done with both politics and social media, I think you deserve to have it explicitly stated.

I am mildly hopeful about the potential of social media to help non conventional or contentious political participation; however, social media is not a panacea for social movements and it can make them grow anarchically and in unproductive ways. However, I am hopeful that new and better platforms will appear in the future particularly tailored for this kind of unconventional participation.

I am highly skeptical about the potential of social media to improve the quality of conventional politics under democratic regimes; at least as long as social media equates to privately-owned walled gardens whose aim is to extract maximum profit from personal intercommunication, and most users engage in slacktivism. As with unconventional politics I hope that new platforms will improve these prospects.

I am a non believer on the feasibility of social media to catalyze democratic changes and make authoritarian regimes stumble. I think that a large part of the discourse on the so-called ‘social media revolutions’ has got a white-savior flavor that is profoundly distasteful and condescending with local populations. Moreover, networked authoritarianism is the best counterexample to the presumed benefits of social media to inspire democracy.

I am extremely worried about the growing movements to exploit social media data in the War on Terror. Because of its own nature, lone wolf attacks are virtually impossible to avoid, and trying to automatically do so will devoid of meaning most of the liberties that define liberal democracies. Indeed, as long as social media are privately-owned platforms legally bound by potentially unjust laws the chances of criminalization of innocent citizens will increase, and the prospects of opposition groups under authoritarian regimes will weaken.

In short, although the interaction between social media and politics is usually described as a new ‘agora’ such an analogy is misleading. On one hand the classic agora is reduced to a marketplace which was not its only role in the classic world. On another hand, while current social media are commercial in nature—like a marketplace—they are not truly public. Actually, a better metaphor for social media and politics would be shouting and throwing pamphlets in a mall while trying to not disturb the clientele and avoiding the security guards.

Thus, my overall position is liberal regarding social and individual issues, but not so much regarding commercial ones. I somewhat distrust privately owned platforms not because they are malign, but because their interests are not aligned with those of citizens.

From my point of view, to be a valid political realm social media requires of free, open sourced, distributed, and decentralized tools which rely on strong encryption and complete anonymity (see the concluding remarks of the book).

Certainly, such an approach could render social media platforms as virtually useless for traditional actors such as political parties, lobbies, and politicians. However, that would not be a bug, but a feature: a problem of current social media is that it has been colonized by elites and transformed a presumed many-to-many conversation in a new form of broadcasting.

Moreover, gauging representative and trustful public opinion would be increasingly difficult if not impossible at all. Yet, it is a cheap price if it means that authoritarian regimes cannot easily monitor dissent groups.

It is also true that terrorist organizations would take advantage of anonymity and encryption but, after all, they are already exploiting the current tools to their advantage, and, in this regard, I think that the words by Benjamin Franklin perfectly apply: “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.”

To end with, which are my goals when writing this book? What am I trying to convey?

I will be clear, I am trying to persuade you that the complacency of the Panglossian scenario (Barber 1998) in social media is dangerous: social media on itself will not make us freer—particularly if controlled by privately-owned corporations. Indeed, such a believe may pave the way for what Barber labeled as ‘Pandora scenario’: the application of technology for control and repression.

In order to persuade you I will try to make you think about social media, not only in its current state but in its past and, more importantly, in its future state. I will try to make you think about politics and democracy beyond the fanfare of electoral campaigns and voting. I will try to help you develop an informed opinion on the current state of social media and politics, and make you consider if such an state of affairs is the best possible one or if there is room for improvement.

Hopefully, I will be able to convince you that a Jeffersonian scenario, no matter how improbable, is feasible, the most desirable outcome, and something all of us should fight for using our means at hand.

1 Political participation

“You might not be interested in politics, but politics is interested in you.”

Robert D. Holsworth

1.1 Introduction

Verba and Nie (1972: p. 1) said the following about democracy and participation:

“If democracy is interpreted as rule by the people, then the question of who participates in political decisions becomes the question of the nature of democracy in society. Where few take part in decisions there is little democracy; the more participation there is in decisions, the more democracy there is. Such a definition of democracy is crude [...] yet it may get at the heart of the matter, since all other institutions associated with democracy can be related to the general question of who participates or is able to participate in political life.”

Political participation is the core of democracy and, as such, it fulfills a number of crucial functions: it allows the citizenry to communicate with their representatives; it affects, in turn, the behaviors of those in response to citizens’ demands; and, finally, it is a source of civic satisfaction “with the government, and [...] with one’s own role” (Verba and Nie, 1972: p. 5).

Little political participation erodes the legitimacy of the actions of the government because a large part of citizens were not involved in the decisions leading to them; it makes the government actions detached of the people’s demands—or, at least, detached from the demands of some parts of society; and this, in turn, negatively affects the satisfaction of people.

Indeed, we have been witnessing this ‘democratic disenchantment’ and a constant decline in political participation for a number of years—some such as Putnam (2000) say that for a number of decades—and it is one of the major paradoxes in modern democracy: while democratic ideals are generally praised, the majority of democratic regimes are subject to constant scrutiny and strong criticism by their own citizens, who show increasing levels of distrust and detachment from political institutions (Rosanvallon 2008). Thus, it is hardly surprising that political participation—or, much better, its lack of—is subject of major research by political scientists.

It must be noted however, that although no political scientist denies this worrisome situation, some of them (e.g., Rosanvallon, 2008: p. 18, or Hay, 2013: p. 23) argue that indicators such as increasing abstention are not necessarily a signal of apathy, but maybe of a change in citizens’ behavior towards more unconventional forms of participation.

In this regard, Rosanvallon says that “voting is the most visible and institutionalized expression of citizenry, the symbol of political participation and civic equality” but it is not the only mode of political participation which is a much more complex issue. In a similar vein Hay (2013) suggests that the only difference between those arguing about the lack of participation, and those arguing a change in modes of participation is their conception of what ‘political participation’ is. Therefore, what is political participation?

Given that I started quoting Verba and Nie, it is de rigeur to include their definition: “those activities by private citizens that are more or less directly aimed at influencing the selection of governmental personnel and/or the actions they take” (Verba and Nie, 1972: p. 2).

Of course, theirs is not the only definition, and other scholars—including Verba and his colleagues—have proposed successive refinements to encompass an increasingly wide spectrum of political actions. Among such definitions, those by Milbrath (1981) and Verba et al. (1995) have been commonly employed in social media research.

Milbrath defined political participation as “those actions of private citizens by which they seek to influence or to support government and politics”, while Verba et al. described voluntary political participation as any “activity that has the intent or effect of influencing government action—either directly by affecting the making or implementation of public policy or indirectly by influencing the selection of people who make those policies”.

This issue, however, is far from settled and, indeed, depending on the considerations about what constitutes or not a mode of political participation very different readings can been made from the same situation. In this regard, the interested reader should consult the recent work of van Deth (2014) who provides an operational definition that can be straightforwardly applied to determine if a behavior (offline or online) is or not political participation.

Nevertheless, for the purpose of this chapter it is enough to know that, according to van Deth, political participation is (1) an action; (2) conducted by particular citizens; (3) voluntarily; and (4) dealing with politics, the government or the state in a broad sense of those terms.

A non exhaustive list of online and offline actions that fit one or more of prior definitions, and that are mentioned in one or more of the papers covered in this chapter, are provided in Table 1 as an illustration. Please note that some of those actions (e.g., ‘visiting political websites’, usually considered the online equivalent to the traditional action of ‘being informed about politics’) were explicitly excluded by van Deth who did not consider them as activities. Yet, he acknowledged that other authors label such activities as ‘latent forms of political participation’. It is important to emphasize that this is not a simple terminological subtlety: I will discuss later the impact that latent aspects of social media engagement can have in offline political actions such as voting.

Table 1.1 Specimens of typical modes of political participation in offline and online settings.

|

Offline political participation

|

Online political participation

|

|

voting

being informed about politics

contacting elected officials (e.g., in person, by phone or by letter)

engaging in political discussion

writing letters to newspapers

sending support or protest messages to political leaders

wearing/displaying badges, stickers or T-shirts with political messages

attending meetings or rallies

persuading others to vote

joining and supporting a party

campaigning for a party or candidate

making financial contributions to a party or candidate or participating in fund-raising

running for office

working with others on local problems

distributing flyers with political messages

giving speeches

signing a petition

deliberately buying (or boycotting) certain products for political reasons

refusing to obey unjust laws

participating in a legal demonstration or strike

writing political messages on walls

participating in an illegal demonstrationrioting

|

looking for political information on the web (including videos) visiting gubernamental or public administration websites

visiting websites with political contents or run by political organizations

signing up for a newsletter, subscribing to an RSS feed

signing up as a friend or following a political organization, an elected official or a candidate on a SNS

downloading materials related to a political organization such as screensavers or wallpapers

customizing a webpage or social media profile to display new political or campaign information

contacting a political official or candidate (e.g., via e-mail)

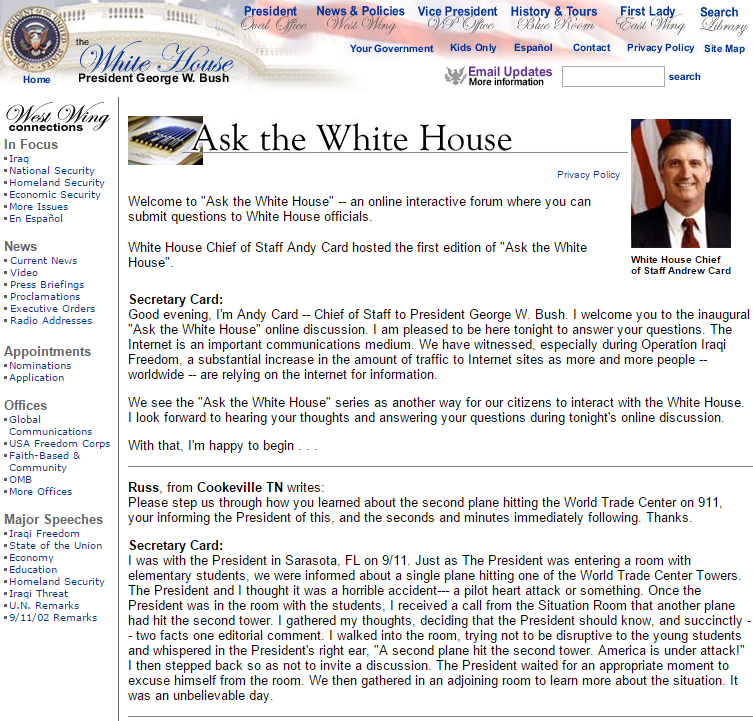

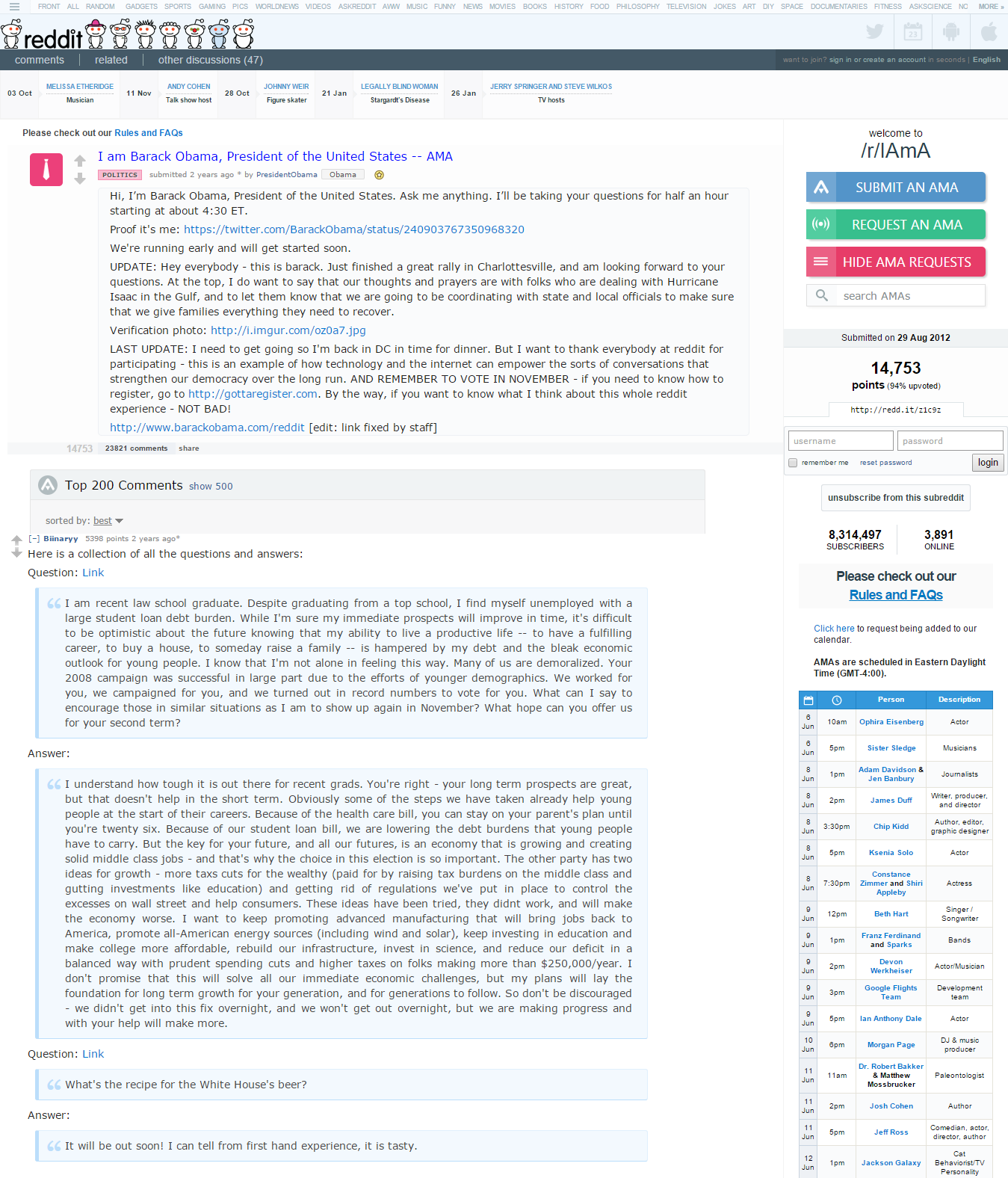

participating in an online Q&A session with a political official

political dialogue/discussion (e.g., chat rooms, email lists, SNS, etc.)

reacting online to a message or article on the Internet (e.g., adding a comment, liking or favoriting it).

posting a message in a blog or microblog expressing a political opinion

creating or uploading videos with a political message (e.g., to YouTube)

starting or joining a political group on a SNS

signing up to volunteer for a campaign

donating online

talking with others about the campaign

trying to influence others (e.g., via e-mail, e-postcards or sharing/forwarding political content by third-parties)

joining a political organization online

working with others in a virtual community to deal with local problems

signing a petition online

participating in online polls

organizing an internet-based boycott or protest

|

Table 1.

Once clarified what political participation is and its importance, it is unsurprising that increasing participation should be actively pursued in democracy, and that a good amount of research has been conducted on the role that social media can play to achieve that goal.

In this regard, two broad lines of research have been explored: (1) Whether social media decreases, increases, or does not affect political participation at large; and (2) whether social media is able to mobilize previously unengaged (e.g., the youth) or disenfranchised people (e.g., the poor and the less-educated).

Depending on the findings—which, in all honesty, are varied to the point of contradiction, the interaction between social media and politics regarding participation can be depicted in a number of ways:

-

The demobilization scenario which posits that social media has a demobilizing effect on people and, thus, it decreases political participation.

-

The mobilization scenario, whose advocates claim that social media is able to move people to take part in politics, especially those who are uninterested in traditional participation, or the disenfranchised.

-

The normalization scenario, which claims that social media just appeals to those who are able to participate in politics in traditional ways. Thus, social media is seen as a complement for offline modes of political participation.

-

The reinforcement scenario, which can be seen as a perverse hybrid of mobilization and normalization. Its proponents argue that politically engaged citizens can get additional advantage over unengaged and disenfranchised people because of using social media.

-

The commodification scenario, which can be considered as a degeneration of normalization; here social media is used as just another mass media and, thus, people’s political participation is basically reduced to information consumption.

-

The null scenario, which states that social media does not increase political participation but just the opposite: politically engaged people tend to use social media to keep on with their political activities. It must be noted, that most of the time the difference between proponents of normalization and null scenarios does not lay on the results but on their interpretation.

Moreover, it is not unlikely that features from most of these scenarios are taking place simultaneously, but affecting different groups of people and with varied intensity depending on many factors, including idiosyncrasies of each electoral or inter-electoral period. Moreover, we cannot rule out the possibility of a mutual interaction between online and offline actions; that is, citizens participating in traditional ways going online and vice versa, users engaging in politics on social media and then moving offline.

In the following sections I will review a selection of relevant literature regarding each of these scenarios. I close the chapter with the broad picture depicted by the interaction between those contending views, in addition to some proposals for further research in the field.

1.2 The demobilization scenario

I include this one just for the sake of completeness because at the moment of this writing there is abundant evidence disproving its most general form, and many of the arguments that have been used to support it lay on heavy-biased readings of the literature.

Its underlying idea is simple—and includes a touch of luddism: Internet alienates people, increasingly isolates persons from their social environment and, hence, it demobilizes them. A less dramatic version lies on the concept of ‘time displacement’: users devoting time to Internet (or social media) are dedicating less time to other activities, such as political participation.

One of the authors most commonly cited in this regard is Putnam; whose work and thinking has been somewhat reduced to ‘television killed civic America’. Certainly, Putnam (1995) said: “Many possible answers have been suggested for this puzzle [the erosion of social capital]: [...] Television, the electronic revolution, and other technological changes.” However, while many have interpreted the ‘electronic revolution’ as a reference to Internet-mediated communications the truth is that Putnam did not simply mention it.

Ideas in that work were later expanded (see Putnam, 2000) and, again, a number of fragments were available for misquotation, and to subsequently blame the computer-mediated communication for the declining in civic and political participation; for instance:

“[U]nlike those who rely on newspapers, radio, and television for news, those few technologically proficient Americans who rely primarily on the Internet for news are actually less likely than their fellow citizens to be civically involved.”

or this other one:

“The absence of any correlation between Internet usage and civic engagement could mean that the Internet attracts reclusive nerds and energizes them, but it could also mean that the Net disproportionately attracts civic dynamos and sedates them.”

However, Putnam did not blame the Internet; although he neither depicted it as the last hope for democracy:

“The timing of the Internet explosion means that it cannot possibly be causally linked to the crumbling of social connectedness described in previous chapters. [...] By the time that the Internet reached 10 percent of American adults in 1996, the nationwide decline in social connectedness and civic engagement had been under way for at least a quarter of a century. Whatever the future implications of the Internet, social intercourse over the last several decades of the twentieth century was not simply displaced from physical space to cyberspace. The Internet may be part of the solution to our civic problem, or it may exacerbate it, but the cyberrevolution was not the cause.”

Other frequently cited work is those by Kraut et al. (1998) who found that although “the Internet was used extensively for communication [...] greater use of the Internet was associated with declines in participants’ communication with family members in the household, declines in the size of their social circle, and increases in their depression and loneliness”. Interestingly, Kraut et al. (2001) found that such effects had later ‘dissipated’ in participants from their original study, and findings in a second study were exactly the opposite: “more use of the Internet was associated with positive outcomes over a broad range of dependent variables measuring social involvement and psychological well-being”.

Another work—this one reporting mixed results from a social media perspective—was conducted by Shah et al. (2001). To start with they criticized reports that depicted Internet use as overall negative (e.g., Kraut et al., 1998), and provided a much more nuanced picture where information exchange had a positive impact in social capital, and social recreation had a negative one. I consider their results mixed because while they found email exchanging (a kind of social media) as positive they also found that MUDs and chat rooms (which are also social media) had negative effects.

In spite of this, more recent studies have mostly discredit the demobilization scenario, at least, as a universal consequence of Internet or social media use. For instance, Jennings and Zeitner (2003) claim that the “pessimistic view that Internet use would somehow lead to a decline in civic engagement is clearly not warranted”, neither the study by DiMaggio et al. (2004) supported the argument of Internet leading to passivity, and Boulianne (2009) found “little evidence to support the argument that Internet use is contributing to civic decline.”

1.3 The mobilization scenario

This scenario is at the antipodes of the previous one. Its advocates claim that Internet (and social media) have a positive impact in political participation affecting every group in society, but especially those that are unengaged or disenfranchised. It must be noted that there seems to exist a real chance of mobilization only affecting those citizens that are already taking part in politics; such a ‘reinforcement scenario’ is not covered here but in another section.

Regarding the mobilization potential of Internet and social media of the population at large, there are a number of promising reports.

Tolbert and McNeal (2003) found that those looking for political information online during the US 1996 Presidential Elections were more likely to vote, even after controlling for a number of factors such as SES, partisanship, and other media consumption; the same effect was found in the elections held in 2000 although not for the 1998 midterm elections. Besides, other political actions such as discussing politics with others, giving money or volunteering for a candidate were also more likely for those being informed online. Similar results were reported by Kenski and Stroud (2006) but they noted that the impact was not large.

Nisbet and Scheufele (2004) conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data regarding the 2000 US Presidential Elections and the impact that Internet could exert on political participation and knowledge. They found a significant, although modest, impact that was increased when the individuals had also discussed politics with friends and family; it must be noted that they agreed that, indeed, it could also be that Internet use could increase offline political discussion and, in turn, political participation. Interestingly, a later work by Hardy and Scheufele (2006) found that online chat rooms had the same mediating impact of face-to-face political discussion to increase political participation.

Stanley and Weare (2004) reported an interesting case study where a Federal Agency created a web-based discussion forum to ask for public input on a strategic campaign; the forum was run in parallel to a docket and it received much more comments, from a more varied range of constituencies, and covering a broader set of topics. It is a quite limited experience but it clearly shows that, at least for concrete issues, social media systems are able to mobilize the citizenry.

Nevertheless, when discussing the mobilizing possibilities of social media it is far more common to suggest that it can help to engage citizens that are uninvolved or uninterested in politics (e.g., the youth or the women), or simply disenfranchised. Purportedly, the low barriers to entry, the relative unimportance of physical location, and even the possibilities for anonymity or pseudonymity would make especially easier for those people to participate.

As with the demobilization scenario, most of the renderings of this optimistic position have got a few favorite references to drop. One of them is Rheingold (1993), the other one is Varley (1991); a typical quotation from the former could be the following:

“The political significance of CMC lies in its capacity to challenge the existing political hierarchy’s monopoly on powerful communications media, and perhaps thus revitalize citizen-based democracy.” (Rheingold, 1993: p.14)

As for Varley, she described a computer-mediated communication system established in Santa Monica, California during the late 1980s to engage citizens in discussions with other fellow citizens and public officials, about different topics of interest for the community. A common quotation reads as follows:

“For instance, through PEN [Public Electronic Network], a group of residents—including three or four homeless—formed an on-line political organization that lobbied successfully for new city services for the homeless.” (Varley, 1991: p. 44)

Without additional context it seems that both authors are rather optimistic and, besides, Varley is describing some exciting results regarding the participation of the disenfranchised. Unfortunately, both of them are usually misquoted and, thus, unfairly criticized—particularly, Rheingold.

Actually, Varley provides plenty of evidence that the system was far from perfect. For instance, she quotes PEN users describing ‘flame wars’, harassment to women, debates dominated by a minority of users, or the lack of meaningful participation by politicians. Taking into account all of this—particularly the abuse against women—it seems far stretched to exhibit PEN as support for the positive impact of social media for political mobilization.

1.3.1 Mobilizing the youth

Anyway, the truth is that there exists plenty of literature arguing about the possibilities of mobilization of unengaged or disenfranchised citizens thanks to social media. However, few hard facts support the general feasibility of this idea; at most, there are cautious remarks about its impact to mobilize young adults, and a number of seemingly promising findings.

For instance, Norris (1999) carefully states that the normalization scenario seems to dominate political participation in the net except for the younger generation; thus, she ventured to suggest that “this may provide some grounds for the mobilization thesis”.

In a similar vein Delli Carpini (2000) argues that Internet can increase and enhance the participation of young adults that are already engaged, or interested but not engaged; he also suggests that it may help “to increase the motivation of currently disinterested and unengaged young adults”, although he points out that such a possibility is less clear.

Ward et al. (2003) draw similar conclusions arguing that the Internet “may bring some new individuals and groups into the political process—notably younger people, many of whom have grown up with the Internet as part of their daily lives.” They also noted that, despite the opportunities for interaction and networking, users tend to perform information gathering.

A number of researchers have conducted cross-sectional studies to find support for these hypotheses, especially regarding young adults, whose disengagement is a matter of concern among political scientists. In this regard, Kroh and Neiss (2009) found a positive effect of Internet use in the mobilization of people below 30; Bakker and de Vreese (2011) found that different CMC systems such as email, forums and SNS positively affects political participation, both online and offline; Oser et al. (2013) found that young adults are much more engaged online than the rest of the population and, moreover, so-called ‘online activists’ are “also involved in offline participation”, and Xenos et al. (2014) claimed that that “social media are positively related to political engagement” of young adults.

1.3.2 Beginning with ‘S’, political participation—Slacktivism?

Regarding social networking sites, Valenzuela et al. (2009) analyzed the relation between Facebook use by young adults, particularly Facebook groups, and online and offline political participation finding a positive, albeit, weak correlation. Very similar results were also reported by Bode (2012).

A similar study was conducted by Vitak et al. (2011) achieving mixed results: They found that Facebook activity, particularly if it was used for political purposes, was correlated with both online and offline political participation; however, they also found that the preferred modes of participation were superficial and with a lower degree of commitment, i.e. ‘slacktivism’ (Morozov, 2009; Carr, 2012).

That conclusion is consistent with prior findings by Baumgartner and Morris (2009) who studied the relation between consuming news through SNS (MySpace and Facebook) and political participation. They found that young adults tend to favour “news that shares [their] preexisting point of view”; that such kind of information does not improve their political knowledge; and it increases online political activity but not offline political actions, including voting intention.

A similar position is hold by Schlozman et al. (2010): they found that social networking sites such as Facebook were actually mobilizing young persons into political online actions but they also argue that “many forms of political engagement on these venues [e.g., friending a candidate] do not fall squarely under the rubric of a definition of political participation” in the sense of aiming to influence the actions of the government.

1.3.3 Political participation without political knowledge?

Even more worrisome that slacktivism is the apparent lack of impact that social media use has got in the political knowledge of young adults. Such a conclusion by Vitak et al. has also been offered by Conroy et al. (2012), and similar findings have been reported by researchers analyzing different social media environments.

For instance, Eveland & Dylko (2012) analyzed the impact of political blog reading during the US 2004 Presidential Elections and found that it was “unrelated to political knowledge”.

Östman (2012) studied the relation between the involvement of young users with user-generated content (namely, the production and consumption of contents in MySpace, YouTube, and blogs) and political participation and knowledge. While UGC involvement can increase political participation it does not seem to affect political knowledge.

In a similar vein, Park (2013) reports that self-identified ‘opinion leaders’ in Twitter are more politically involved, more verbal, and they have got more followers than non leaders but, surprisingly, they do not consume more news than them. In other words, young politically involved Twitter users are not better informed than the audiences following them.

1.3.4 Mobilization of other groups

Regarding other unengaged groups apart of youth, Krueger (2002) found an intriguing negative relation between online political activity and family income: apparently, those individuals with lower incomes (and, thus, a lower SES—Socioeconomic Status) were much more engaged online in comparison to those with higher incomes. Hence Krueger ventures:

“[T]he anonymous nature of the medium allows those from lower status groups to feel more empowered in an online environment compared to analogous offline interactions [and] by drawing on a different set of resources, the same individuals may not be disadvantaged online, thereby potentially expanding the scope of those participating in politics”.

Similar claims were made by Gibson et al. (2005) who found that women and people from poor backgrounds were “equally likely to engage in online participation in general as men and higher social status individuals, once existing levels of political involvement and experience on the Internet are taken into account.”

There is an important caveat to such encouraging findings: Krueger himself points out that Internet access heavily depends on income and, thus, “without equal access, the medium will continue to advantage those types of people already engaged in politics”; moreover, other researchers found just the opposite: “the effect of the Internet is, contrary to the expectations, stronger in citizens with high income” (Kroh and Neiss, 2009).

In addition to that, there are also some daunting findings made by Hoffman (2012) in relation to the online and offline political behavior of those less educated. To start with, she distinguished between ‘political participation’ and ‘political communication’, two sets of actions which are usually conflated in virtually all of the studies. As examples of political participation she suggested ‘contributing money online’, or ‘starting or joining a political group on a SNS’. On the other hand, tweeting, discussing with others about politics using email or text messaging, or posting political material in any sort of social medium, are examples of political communication.

Taking into account such a distinction and performing a cross-sectional study, she made two surprising findings: (1) online political participation predicts voting but online political communication does not; and (2) online political communication is negatively related to education. In other words, less educated users discuss about politics more than other users, but such discussions do not have an impact on voter turnout.

1.3.5 ‘Subliminal’ mobilization?

All of the studies mentioned so far lay on the assumption that users are mobilized because of the more or less ‘explicit’ interactions they have with other users on social media (e.g., they discuss with others, they receive and forward political information, etc.) However, it is also possible that mobilization occurs because of users incurring—although barely noticing it—in latent political participation.

To the best of my knowledge, one of the first authors noting this possibility was Gustafsson (2012) who said regarding politically unengaged Facebook users:

“[P]assive users were also affected by recruitment attempts, by things they saw that their friends did, links their friends posted, and so on. It is time that the distinction between manifest and latent participation is brought into the research field.”

Barely five months after the publication of his work, another publication by an independent team revealed that some kind of ‘subliminal’ mobilization seemed feasible.

Bond et al. (2012) describe a randomized controlled trial where two groups of Facebook users received a message to encourage them to vote in the US 2010 midterm elections, and that also included an ‘I Voted’ button. In one group (1% of the eligible population) the message was purely informational: it just reported the number of friends that had clicked the button, while in the other group (98% of the population) it also showed a random selection of faces of the user’s friends who had already voted. The control group (the remaining 1%) did not receive any message.

The researchers found that both messages were able to mobilize users to click the button, but the so-called ‘social message’—the one with the friends’ faces—spurred more mobilization, it spread farther across the user’s social network, and it had an actual impact on voter turnout. And let’s not forget that the only difference between both messages were the faces.

This research raises additional questions. First, it opens an ethical and legal debate about the implications for social media sites—a debate which is totally out of the scope of this chapter; secondly, it makes one wonder about the myriad of subtle details imbued in social media interactions that may impact others’ political actions.

1.4 The normalization scenario

The normalization of political participation in social media has been approached from two slightly different perspectives. The first one suggests that Internet and social media will be just another channel that will supplement but not replace, nor expand, the possibilities available through other channels. Therefore, people will eventually use the available medium which is more appropriate for the action at hand, according to their interests and skills.

Wellman et al. (2001) can be considered a representative of this position, but similar claims about social media supplementing (while not replacing) offline political actions were made by Shah et al. (2005), or Gibson & Cantijoch (2013).

The other approach to normalization is not so focused on the media but on its users; particularly on their demographic traits, and whether they are different or—much more likely—similar to those of citizens traditionally interested in politics. Actually, this normalization perspective claim that political users of social media will be extremely similar in terms of socioeconomic status to politically engaged citizens, although advocates of this version of ‘social media normalization’ admit that they may be younger.

A number of researchers have supported this position. For instance, Norris (1999) notes “the appeal of the net for the more affluent and more educated”; while Krueger (2006) found that “those with the characteristics that predict conventional mobilization continue to hold a mobilization advantage in the new technological environment; only the mechanism by which they gain an advantage changes.”

This second interpretation of normalization is extremely important because, as Krueger points, it could be that political participation through social media could bring larger inequalities.

1.5 The reinforcement scenario

If social media was just another realm for the engaged citizens to participate in politics then it would simply keep the status quo; i.e., unengaged and disenfranchised citizens would not participate neither offline nor online, while engaged and enfranchised citizens would use any of those options.

However, if social media actually provided an advantage—no matter how small, then such an advantage would be played by those that are already advantaged over those who do not even participate in traditional ways. Hence, depending on the degree of that presumed advantage, social media would deepen the inequalities already present in our democratic systems.

Norris (2001: p.238) is one of the first scholars warning about the risk of social media reinforcing only those persons already interested in politics; later, a number of researchers have provided factual support for such an hypothesis by means of surveys, longitudinal, and cross-sectional studies; for instance: Jennings and Zeitner (2003), Weber et al. (2003), DiMaggio et al. (2004), Di Gennaro and Dutton (2006), Kroh and Neiss (2009), Schlozman et al. (2010), or Oser et al. (2013).

The commodification scenario

As with the reinforcement scenario, the commodification of social media regarding political participation is more a possible consequence of its normalization than an scenario on its own. In fact, one of the first scholars depicting such an outcome—Resnick (1997)— was actually describing it as ‘normalization of cyberspace’.

His position was simple: both utopians and their idea of cyberspace empowering people, and dystopians fearing cyberspace would imply control and repression were wrong. He argued that Web access was transforming cyberspace from a text-based realm with limited access into another mass medium appealing “to the economic, social, and political forces that had previously ignored it.” In this regard he said:

“Cyberspace has not become the locus of a new politics that spills out of the computer screen and revitalizes citizenry and democracy. If anything, ordinary politics in all its complexity and vitality has invaded and captured Cyberspace.”

In other words, the Web made cyberspace universally appealing and, thus, it was to mostly mirror the same virtues and evils of the offline world, including of course political activity. Resnick’s position contains a number of interesting and pessimistic arguments that, although unsupported by data at the time of his writing, have been proven rather far-sighted.

He claims, for instance, that newsgroups and listservs may have been a realm of passionate, individualistic, and egalitarian discussion, but organized groups such as political parties would seldomly reply to posts in such environments because “these groups are not seen as the main vehicles for influencing a mass public.”

Resnick depicts the Web, or better political websites, as the favoured way to reach “the public which is ripe for persuasion and manipulation [...] [the] free-floating agglomeration of Web surfers and searchers.” That is to say, Resnick considers that the deliberation possibilities of cyberspace are irrelevant because it would be transformed in another broadcasting medium; and it would be so because of “the harsh reality of masses of bored and indifferent citizens”.

Resnick’s harsh prospects about this consequence of the normalization of cyberspace were not unique; in fact, slightly earlier than him McChesney (1996) said:

“Aside from the question of access, bulletin boards, and the information highway more generally, do not have the power to produce political culture when it does not exist in the society at large. Given the dominant patterns of global capitalism, it is far more likely that the Internet and the new technologies will adapt themselves to the existing political culture rather than create a new one. Thus, it seems a great stretch to think the Internet will politicize people; it may just as well keep them depoliticized. The New York Times cites Wired magazine approvingly for helping turn «mild-mannered computer nerds into a super-desirable consumer market,» not into political activists”

Hence, an even more worrisome consequence of normalization than greater inequality is this undesirable transformation of social media, where its potential for many-to-many communication is reduced to an unending variety of one-to-many channels offered by organized groups, corporations, and celebrities.

Needless to say, McChesney and Resnick were not the only scholars that noted such commodification as a factor that can make it eventually unfeasible as a meaningful political tool: see, for instance, Rheingold (1993: pp. 301-306), Buchstein (1997), Thornton (2001), or Dahlberg (2005).

Given that at the moment of this writing virtually all major social media platforms are privately owned, the commodification of social media and its potential impact for political participation is an extremely relevant issue, albeit still an open one.

1.6 The null scenario

Strictly speaking, the null hypothesis should refer to the lack of any impact on political participation because of social media use. However, the truth is that an extremely large number of studies have found such an impact—actually, a significant positive correlation between interactive online activities and political actions. Therefore, those criticizing the argument about the positive impact of social media in political participation disagree in how significant such impact is, or in the direction of causality.

In short, critics claim that the impact of social media is weak, or that it is not social media the cause for political participation but just the opposite: politically engaged people use social media as another realm for political actions, and that is the reason for the observed online behaviors.

An additional problem is that most research must rely on cross-sectional studies. Such a limitation is almost unavoidable and, indeed, researchers have used the best available data which is not suitable for longitudinal studies—which are able to find differences before and after the treatment, in this case being engaged with social media.

Nevertheless, a few analysis of this second type have been conducted and, on those bases, some argue that the hype and hope about political participation being increased by social media should be tone down a little.

For instance, Jennings and Zeitner (2003) relied on survey data collected during the years 1965, 1973, 1982, and 1997 for a 1965 sample of high school seniors. Such data contained many details about political participation before—1982—and after—1997—the Internet; and, in addition to that, the data corresponding to 1997 also included surveys of part of the offspring of the original panel. Moreover, the social media types covered in the questionnaires were pretty varied: Usenet news, listservs, chat rooms, WWW and other computer services.

Some of the conclusions of their study were not especially surprising such as finding that the younger generation was using Internet much more than its parents, and that its political use of the medium was even higher. Others were rather interesting such as their suggestion that it is not Internet use what drives political participation but the opposite; in this regard they say: “other factors, most especially previous levels of civic engagement, are generating this relationship between political involvement and political use of the Internet.”

Kroh and Neiss (2009) worked on both cross-sectional data and a natural experiment based on the unequal deployment of home access to broadband Internet (both in Germany). Their analysis of such sources of data led them to conclude that the correlation between Internet use and political participation found in cross-correlation studies is mostly due to self-selection, i.e. citizens who are politically active tend to use Internet more than disinterested persons. Their longitudinal study supports that conclusion and they suggest “that only a small fraction of the correlation is attributable to a causal Internet effect”. This work is mostly consistent with the findings of Jennings and Zeitner (2003), although it does not exclude the causal impact of Internet: it only cuts down its impact.

Bimber and Copeland (2013) also performed a longitudinal study with data from the American National Elections Studies covering the 1996-2008 period in the United States obtaining mixed results. They found no significant correlation between Internet use and political participation in the period 1996-2004, and correlation between such use and a few political activities in the period 2000-2008, particularly ‘trying to persuade others’. They posit that the impact of Internet use on that particular kind of action, combined with the fact that such a correlation was strengthening across the entire period, could be due to “the emergence of social media during the mid-2000s, which are especially conducive to political discussion”.

1.7 Conclusions

Given the abundance of literature about social media and political participation you may be wondering if it has not been subject to any meta analysis. Fortunately, such a meta analysis exists; unfortunately, it depicts a complicated relationship between social media and political participation, to say the least.

Shelley Boulianne (2009) analyzed 38 different studies about Internet use and traditional political participation broadly covering the period 1995-2005, and she found no evidence supporting the demobilization hypothesis. Instead, she found evidence of a positive correlation between Internet use and political participation that seemed to increase across time. She was cautious however, noting that the effect was weak, the increase non monotonic, and the direction of causality unclear. All of this is mostly consistent with the findings of Krohn and Neiss (2009), and not entirely inconsistent with the findings of Bimber and Copeland (2013).

Going beyond that comprehensive survey, when putting side by side the research conducted during the last decades it is poignant how few things can be said about this topic with enough confidence, namely:

Social media is not diminishing political participation; besides, it could help to engage those citizens who are not interested or disenfranchised, particularly if it is used not just for information gathering but to discuss political matters.

However, such an scenario has a number of requirements that are improbable by just relying on market forces (McChesney, 1996). Moreover, while the opportunities that social media offer to disenfranchised and unengaged to participate in politics are important, they are even more so for those engaged and enfranchised.

In other words, social media on its own is unlikely to mobilize previously unengaged people in enough numbers while it is very likely to maintain the status quo, and not unlikely to reinforce it—i.e. widening the participation gap between those engaged and enfranchised, and those unengaged or disenfranchised. There are, however, a few concrete exceptions to that overall normalization-reinforcement scenario.

On one hand, young adults seem to be actually moved by social media to participate in politics; the main caveats are that their political knowledge is poor, and that there is a very real risk of slacktivism being their major mode of participation.

On another hand, while disenfranchised people are not those who have the most to gain from social media, parties and social movements targeted at their needs can benefit from social media use (Norris, 2001: p. 238) and, in turn, give them a voice.

Commodification of social media is, however, the most worrisome problem because it can effectively degrade the most important feature of social media, namely, its potential for many-to-many communication.

All of these phenomena are taking place simultaneously, affecting different groups at different moments, and with different intensity.

A final conclusion is that although research is abundant, it has been conducted in such a fragmented way that makes extremely difficult to paint a meaningful picture.

To start with, most of the research conducted up to date makes direct comparisons almost impossible: there is little overlap between the modes of action that are considered political participation in each study (both online and offline); there are important differences in the populations and subpopulations subject to study; and some research was conducted in relation to major elections while other was conducted without any major election in the horizon.

On top of that, the literature has mainly focused in the United States and, thus, it is difficult to determine if the findings can be generalized to other countries—particularly, new democracies.

Finally, most of the research relies on cross-sectional studies and, thus, the direction of the causality link is subject to discussion: i.e. is social media use causing political participation or is the intent to participate, such as deciding a vote, the cause for social media use? With the evidence at hand the most we can say is that if social media is really causing political participation the impact is very weak.

To sum up, further research is needed on this topic but it has to:

1. Determine a minimum range of actions (both online and offline) that define political participation and that, in the case of social media, are stable enough in time, and broadly generalizable across platforms. Those actions should cover both conventional and contentious modes. Researchers should adhere to those ostensive definitions of political participation and not change them without justification.

2. Pay more attention to other countries in addition to the United States, particularly to new democracies and poor democracies.

3. Clearly separate studies conducted in electoral and in non electoral periods.

4. Clearly target different groups of interest such as young adults, minorities, disenfranchised citizens, etc.

5. Aim to conduct longitudinal studies in addition to cross-sectional ones to better determine both the direction of causality and its impact.

6. Aim to develop measures of intervention to shrink the participation gap between engaged and unengaged people or, in other words, try to make the reinforcement scenario less likely and increase the chances of mobilization.

Needless to say, none of those requirements is easy, and, on top of that, the last one could be a matter of ethical and legal concerns. However, given the crucial importance of political participation and the pervasiveness of social media use, citizenry is entitled to a more substantial answer from the research community than ‘it’s complicated’.

2 Political actors

“Any person or organization depends ultimately on public approval, and is therefore faced with the problem of engineering the public’s consent to a program or goal. We expect our elected government officials to try to engineer our consent for the measures they propose. [...] The engineering of consent is the very essence of the democratic process, the freedom to persuade and suggest.”

(Bernays, 1947: p.14)

2.1 Introduction

Previous chapter rested on the premise that the more political participation of the citizenry the better the democracy. Thus, it discussed a number of modes of participation, as well as the impact of social media on them. The underlying idea is that, no matter the concrete ways of taking part in politics, individual citizens can and must influence the government decisions. In this regard political knowledge is fundamental—although it was not discussed at depth—for citizens’ actions being informed. It was also implied that the definite political action of citizenry is voting, and that votes eventually drive government.

Yet, I did not fully explore what ‘voting’ is. In that regard, I must briefly recall that democracy can be implemented in two rather different ways: representative and direct. Virtually all modern liberal democracies are of the representative kind, although some instruments of direct democracy—such as referenda—can be employed more or less frequently. Therefore, and simply put, in its most usual sense ‘voting’ refers to citizens choosing their representatives for government.